Is safety the best course of action? Our grandparents were willing to sacrifice their lives to preserve freedom for future generations. Our generation is sacrificing children’s futures to protect our lives… There is something terribly wrong in this equation and to me, it feels cowardly.

Our societies appear to be labouring under the belief that safety is the most important value to possess.

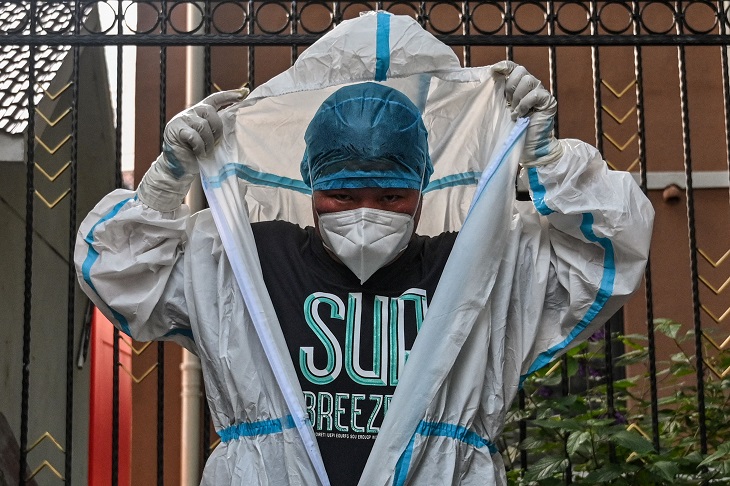

In public spaces, there are imprecations that ‘your safety is our top priority’ and entrances to all buildings are besmirched with myriad posters with details about viruses and hand hygiene. Who actually reads these is anyone’s guess, but there they remain a symbol of public health and government outreach. Indeed, one of the more common greetings we encounter is ‘stay safe’.

I don’t want to stay safe – I want an appropriately risky day for the activities I have chosen to undertake. Although I admit, that sounds less pithy.

Ultimately, Safetyism is an example of what Thomas Sowell might call ‘stage-one thinking’. Namely, a theoretical solution to a theoretical problem is implemented without anticipating the consequences.

Sadly, so-called ‘stage-one thinking’ appeals to politicians as the messaging is simple. ‘Risk is bad’ and our party’s intervention will reduce this risk. Invariably we do not know if 1) said intervention does reduce said risk 2) there are adverse effects of said intervention or if 3) the costs outweigh the benefit.

I submit that having safety as the priority is a poor mantra.

On one level, there will always be a trade-off between safety and convenience, thus in most domains we accept a certain level of danger to have convenience in our lives. Though none of us want to disregard safety as a principle, for many of us it is the danger of certain activities which makes them fun and exciting.

The element of individual assessment is key to this. Imprecations of safety for someone in their eighties are going to be very different to a healthy eighteen-year-old. The priorities and the risks will be very different. By having a blanket policy of safety for all of society we do not admit this difference and we risk harming our young and healthy people through Safetyism.

It is especially relevant as, over the last decades, we have seen the results caused by over-protecting children from risk as they develop.

In order to grow as humans on a social, psychological, and immune-physiological level, we need to expose ourselves to reasonable risk. The consequence of this has been a generation of young adults who are ill-equipped to defend themselves by means other than censorship (see Jonathan Haidt).

It is damaging on so many levels to protect someone who does not need protecting. The same principle allows us to improve at our jobs; especially in medicine, it is only by being out of our comfort zone that we learn new skills and improve as clinicians.

Benjamin Franklin said, ‘Those who would give up essential liberty to purchase a little temporary safety deserve neither liberty nor safety.’

We each have our own takes on this, but there is something cowardly in society about having too much of a focus on safety. Without saying we should court danger, to live life in perpetual fear of an existential threat is no way to live.

It is ignoble and dehumanising to have safety as the pure priority, for safety is not what gives life meaning. It is interactions with fellow humans, sports, activities, social groups and religions, jobs, and voluntary exchange which gives our lives meaning, and these involve risk. Safety is incidental and can either facilitate or curtail these activities. To have such a disproportionate focus on safety is to sacrifice our humanity and the meaning in our lives for an indefinite end.

Increasingly, in medicine we have been shifting towards a holistic model of care, where we are not just asking how to most extend a life or cure a disease, but rather, how can we provide an individual’s life with the most meaning. It asks how we can care for a patient by considering their concerns and wishes.

We accept some people for joint replacements despite the risk of surgery because the improvement in quality of life for them may outweigh any risk of surgery. We also do not always treat illnesses towards the end of life because the treatment will cause more suffering than the disease running its course. Indeed, a lot of the time we chose not to investigate low-risk conditions is because the investigations themselves may cause harm and are unlikely to show anything.

With every decision there is always risk, what matters is if this is justifiable.

Why the emphasis now? Perhaps the exigencies of a pandemic warrant this. Perhaps the damage to healthy populations by safety measures is justified by the benefit to at-risk populations. On the other hand, perhaps Safetyism is the easiest way for a government to avoid addressing complex and difficult questions – the easiest way to appear proactive whilst avoiding the issue. At what expense does this come?

Just as an individual needs risk exposure to develop themselves, our societies do as well. We can purchase temporary safety from disease, from industrial accidents, from corruption by a burden of regulations and rules. This comes at the expense of our future; as our society starts to stultify, we stop taking risks, we stop investing, and we stop providing for the future. Instead, we develop a high time preference, thinking of the present and thinking of ourselves.

Our ancestors sacrificed themselves to protect future liberty; we are sacrificing liberty to protect ourselves, perhaps we are cowards after all.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in