The concept of vaccination evolved from 18th-century inoculation practices and many people contributed to the accretion of knowledge. This book focuses on two individuals: the Quaker doctor Thomas Dimsdale, who, from his small Hertfordshire surgery, pioneered a simple smallpox immunisation; and Catherine the Great, who summoned him all the way to St Petersburg to inoculate her and the teenage Grand Duke Paul. Despite success all round, though, it turns out that anti-vaxxers are nothing new.

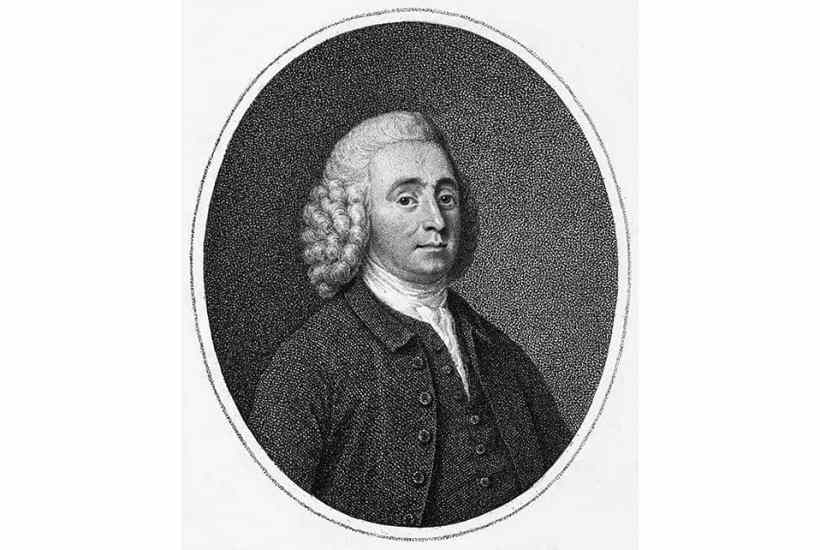

After revealing the destructive force of smallpox – in one period of the 18th century, 400,000 perished annually in Europe – Lucy Ward, a journalist and former lobby correspondent, recapitulates the history of inoculation against the disease. The innovative Dimsdale worked to refine the practice of infecting patients with a controlled viral dose to ensure future immunity. He published a landmark treatise on the subject in 1767.

As the story unfolds, Ward writes of the first known example of the use of numerical quantification to evaluate medical endeavours, as opposed to subjective opinion based on just a few cases. As she says, although ‘medicine came somewhat belatedly to the empirical approach’, as the century wore on ‘the ground on which knowledge was built was changing irreversibly’.

After George I had his grandchildren jabbed (all subsequent Hanoverians were inoculation enthusiasts), word of Dimsdale and his prowess spread across Europe. The Empress and the English Doctor shifts between England and Russia until the bewigged Dimsdale and his son trundle off in a carriage to St Petersburg in 1768. Ward fills in her protagonists’ backgrounds, including Dimsdale’s expulsion from the Quakers and the arrival in Moscow of the 14-year-old German Princess Sophie Friederike August of Anhalt-Zerbst (later the Empress Catherine). Her marriage was traumatic. Ward comments gnomically: ‘There is no evidence Catherine ordered her husband’s death.’

‘Her aim was to challenge prejudice and promote science,’ Ward suggests, as the empress submits to the scalpel. Catherine succeeded in both, and developed with Dimsdale what Ward calls ‘a bond of respect’. The pair had a ‘shared mission’: the doctor was determined to take his inoculation campaign to the poor (‘at heart he was a reformer’) and the rouged Catherine also planned reform, as ‘a broader conception of public health was emerging, and it was seen as the business of the state’. In St Petersburg Dr Tom sat on the royal bed chatting with the Empress of all the Russias while her lover Count Grigory Orlov snoozed beside them.

Ward maintains the pace as tense days pass after the inoculation and pustules appear around the incisions. Once the patient rallies, the court goes inoculation crazy, Catherine declares war on the Ottoman empire and Dimsdale receives £10,000, ‘the equivalent of around £20 million in income today’. He spent seven months in Russia, and returned to take a seat as MP for Hertford.

Ward has mined the primary sources and quotes judiciously from Dimsdale’s letters home and Catherine’s detailed memoirs. But the prose tends to a fictionish purple: ‘The Dimsdales were awestruck by the city’s magnificence and unfamiliar, fairytale beauty.’ There are also anachronisms, such as ‘crowdsource’, ‘crunching numbers’ and ‘on-message’. Overall, the book is a combination of arcane detail and the high colour of a period drama. The story would certainly make a fine film.

Ward follows the empress’s successful inoculation with chapters titled ‘The Impact’ (‘What a lesson your imperial majesty has given!’ Voltaire wrote to Catherine), ‘The Celebrity’ (Catherine made Dimsdale a Baron of the Russian Empire) and ‘The Legacy’. In France Louis XV was among the few rulers who refused inoculation. He died of smallpox at Versailles in 1774, the fifth reigning European monarch the disease killed that century.

Others get credit in the overall saga, before and after Dimsdale. Lady Mary Wortley Montagu, a gripping figure, brought news of Turkish ‘smallpox parties’ at which families practised an early version of inoculation, and she presided over the first official immunisation in Britain. Then, of course, in 1776 the fabled Edward Jenner, a Gloucestershire doctor, drained pus from blisters on a dairymaid’s hand and transferred it into the arm of his gardener’s son – a procedure which became known by a new name, based on the Latin for cow, vacca.

Britain was the first European country to adopt inoculation, and the first to grant the practice official approval. The country then led the way in developing and deploying a revolutionary new method of administering it. Despite that, 300 million died of the disease in the 20th century before smallpox itself died and the WHO declared the planet smallpox-free in 1980. As for the 18th-century anti-vaxxers, they fought hard against Dimsdale and his reforms for no decent reason. Ward writes that ‘today’s vaccine scepticism’, like the ignorance permeating public life in Dimsdale’s Enlightenment, ‘holds up a mirror to the times’.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in