There has been much rejoicing over falling unemployment – something undoubtedly better for the government with fewer welfare payments and more tax receipts.

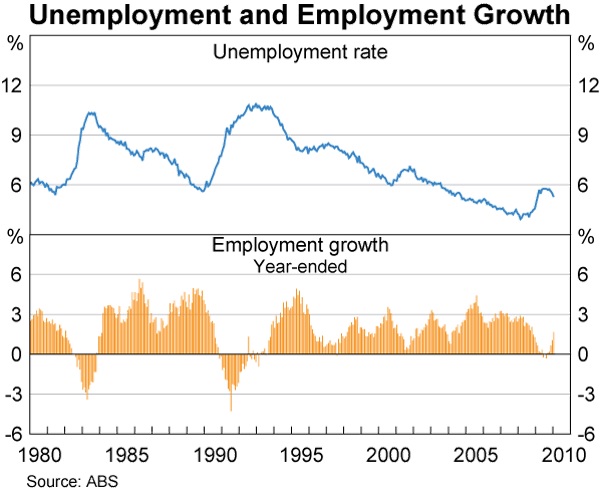

Pre-Covid, a figure of around 5.5-6 per cent (as below) was considered the norm for this country. With lockdowns and restrictions, this temporarily rose as high as 7.5 per cent in 2020, before falling to the latest figure of 3.9 per cent.

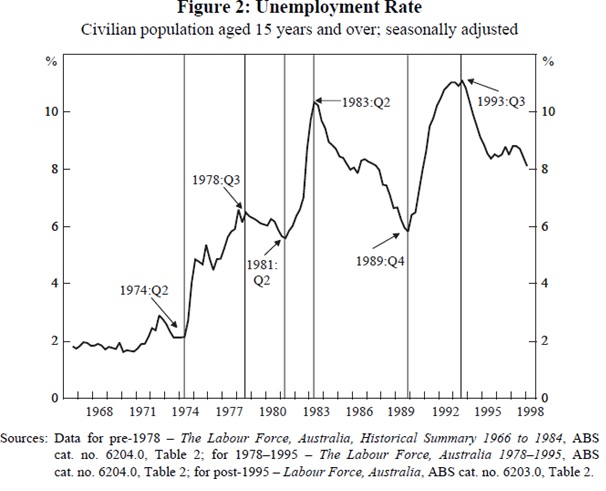

Much is made of the fact that this is the lowest rate since 1974, but many jobs are unfilled and all is perhaps not what it seems.

Previous recessions in Australia have been associated with even worse figures, typically as high as 10 per cent, but in the 1960s, unemployment as low as 2 per cent.

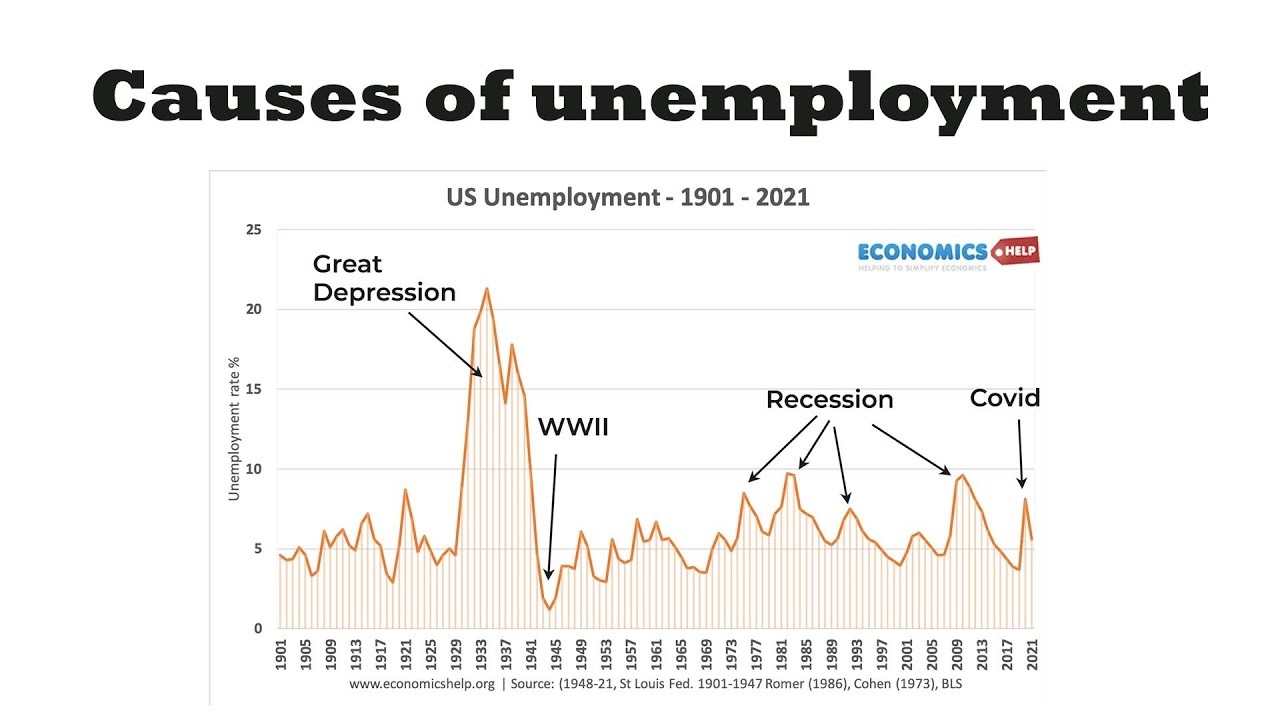

These figures show the effect of worldwide recessions, something we are possibly heading towards now. American figures (as below) show the effect of the GFC in 2008 and other events.

Going back further in history, we see a different attitude to unemployment compared with now. The UK was the second country to introduce some sort of dole payment for those temporarily out of work. Prior to this, it was no job, no food.

With the threat of Communist uprisings, Germany established a scheme in the late 1800s; The UK’s first attempt was then National Insurance Act of 1911, ably supported by Winston Churchill. This took a small amount from workers, employers, and the government, to cover a period of 13 weeks. It applied only to those who were wage earners – at that time less than 70 per cent of the workforce. One reason for its introduction was to improve the fitness of the general population, with 50 per cent of military recruits deemed unfit for service.

In 1920, the scheme was extended to cover a period of 39 weeks, and was a life-saver in the great depression of the 30s. After the second world war, Australia introduced its unemployment benefit scheme, and in the UK a comprehensive welfare system was introduced.

The scheme was intended as a short-term measure to help those temporarily out of work. Like many welfare schemes, it has become a multi-generational way of life for some.

Attempts at resolving this long-term unemployment were made with John Howard’s ‘mutual obligation’ proposals that required the unemployed to engage in study, volunteer activities, join the military reserve or find part-time work. The obligation commenced at 3 months for teenagers and 1 year for adults. It was intended to encourage the work ethic and provided a small supplementary payment; the idea was good but the outcome was poor.

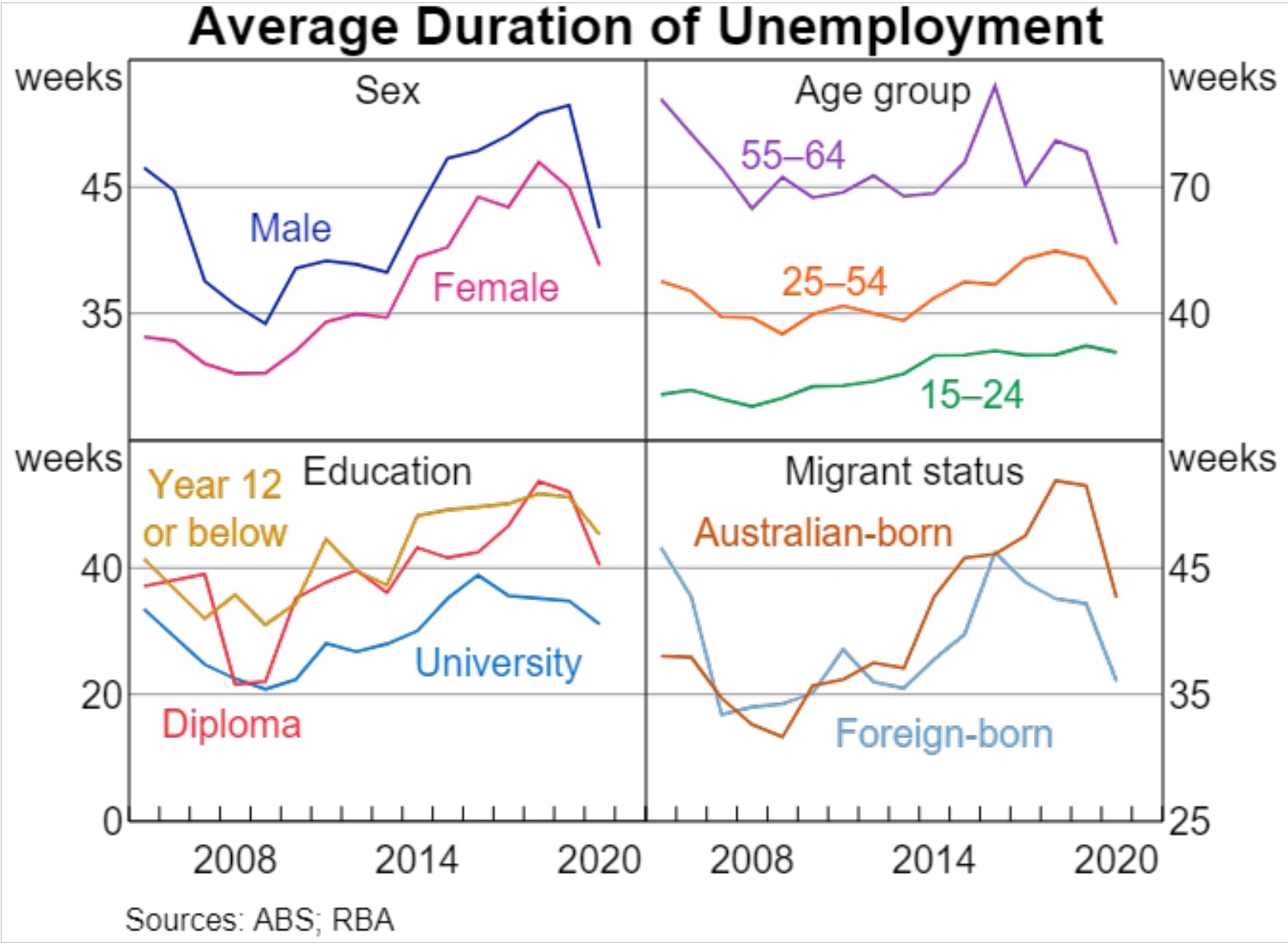

As the graph above shows, the problem groups are older, poorly educated, and Australian-born. Apart from the obvious financial disadvantage, this group has poorer physical and mental health, children with lower academic achievement, and higher rates of crime and violence. A study of the generous Danish welfare system has confirmed bad parenting, with a lack of encouragement of self-reliance, moderation, and the importance of work condemns the next generation to a life of dependency.

In this country, one-third of the unemployed are long-term unemployed (June 2021), this compares with 1 in 5 in 2020 and 1 in 8 in 2010. Comparison with UK shows a current (2022) unemployment rate of 4.1 per cent, with 0.8 per cent long-term unemployed, around 1 in 5. The EU has an unemployment rate of 6.2 per cent, with over 1 in 3 long-term, the ratio has been as high as 1 in 2; figures for the US, with its limited unemployment benefit of six months, show unemployment at 3.6 per cent, with 1 in 5 long -term.

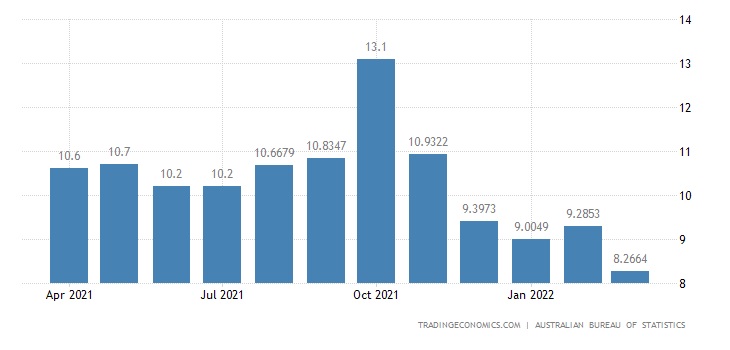

Youth unemployment has also always been a concern, worsening with the pandemic; the historic figure had been around 14 per cent, but had fallen to 10 per cent before COVID, this compared favourably with the OECD average of 16 per cent. At the height of the pandemic, it reached over 13 per cent, now (April 2022) down around 9 per cent, as above, the rate is double for those in the lowest socio-economic group. Comparative figures for other countries show Japan at 3.9 per cent, US 8 per cent, New Zealand 10 per cent, and European Union 14 per cent.

South Africa’s figure of 69 per cent is due to a lack of work, Australia’s is not due to a shortage of jobs. Hospitality and agriculture have particularly been struggling to find workers; government schemes have provided for 23,000 Pacific Island workers to fill some gaps. With a total of over 400,000 job vacancies available, many are suitable for work experience for the 140,000 youths unemployed. The government has a number of schemes, such as work for the dole, to help the young into work, but previous attempts have not been successful. Meanwhile, the historic easy solution is to encourage massive immigration, rather than get people back to work.

The unemployment statistics can also mislead without considering the participation rate, the number of working age (historically measured as 15 to 64) actually in work. In the 1980s, this averaged around 60 per cent in recent years this had risen to around 66 per cent – currently 66.3 per cent – from the Covid low of 63 per cent. The worldwide participation rate is around 75-80 per cent in Europe; Switzerland leads the pack at 85 per cent. The devil in the detail is that this really means that 13.3 million are employed, 1.1 million potential workers are unemployed, and a further 1.2 million are under-employed – not so impressive, although an advance on those earlier years.

What all this means is that although employment has increased in Australia, it remains comparatively poor by international standards. The worker participation rate remains unimpressive, long-term unemployment is too high, and youth apathy and disinterest in labour is apparent. The prospect of having to work, spending 20 hours a week stacking supermarket shelves, to get the dole produced the inevitable outcry from Australian Council of Social Service, but perhaps a bit more stick is necessary.

These deficiencies may become more relevant as the Covid hangover expands inflation looms and electricity prices go through the solar-panel covered roof. The Labor government will encourage unsustainable pay rises, adding to the likelihood of recession, and an unemployment crisis like the 2008 GFC. If we were to reach 10 per cent unemployment again, we will not need extra workers from overseas!

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in