In February 2020, I was invited on to the BBC’s The Big Questions to debate the topic: ‘Is wokeness the new religion?’ I had already anticipated that mine would be the unfashionable view, and so I steeled myself in advance for the inevitable onslaught. This being a British daytime television show, the onslaught took the form of audible grumbles and a few raised eyebrows.

One of my fellow panellists expressed her dismay that we were discussing this topic at all, which is akin to accepting an invitation to a birthday party and then complaining about the bunting. Finding myself drawn into the whataboutery, I agreed that I would much rather be delving into other matters – economic inequality perhaps, or the life and work of Nana Mouskouri – but given that the subject matter had been set in advance, it seemed churlish to grumble now. Another panellist – some breed of activist whose whole body appeared to be stuttering with anger – spat out a few of the usual accusations. Didn’t I understand how important it was to oppose racism? And wasn’t I simply profiting from a culture war that I was deliberately helping to stoke?

Well yes and no, in that order. Apparently this twitching fellow had written a book on ‘anti-racism’ and had received threats following its publication. When I pointed out that I too had been threatened online, his immediate retort was ‘Good!’ As the audience collectively squirmed, evidently unprepared for what happens when the good guy turns bad, he attempted to back-pedal by suggesting that our common experience might facilitate further dialogue. It was too late; his instinct had betrayed him.

Not that he was entirely to blame. Those of us who have taken a critical stance on the culture war in the hope of hastening its demise have often been misinterpreted as attempting to prolong it. For a considerable period of time, most people were happy to dismiss such matters as the niche obsessions of trolls prowling the dark recesses of the internet, or over-zealous students hankering after a cause. In the green days before the coronavirus lockdowns, it was tempting for commentators to hold fast to the received wisdom that the culture war was merely a distraction advanced by unscrupulous politicians. My appearance on The Big Questions took place a month before the global chain reaction of coronavirus lockdowns, and three months before the death of George Floyd and the subsequent protests. Were the debate to be replayed today, it is unlikely that my perspective would be deemed marginal. Few would now deny that the culture war has exploded into the mainstream, and all of us are implicated, whether we like it or not.

The question of whether or not ‘wokeness is the new religion’ is unlikely to feature as a topic for debate these days. For all its flaws, the analogy is now commonplace and many pundits speak freely of ‘the religion of social justice’ without any need for further qualification. Culture warriors of all stripes have become increasingly doctrinaire and sectarian. Many of them favour slogans as a substitute for thought, almost as a form of holy writ. They have their own esoteric language, originating in largely outdated postmodernist jargon, and enshrined in foundational holy texts by the likes of thinkers such as Michel Foucault and Judith Butler, or the intersectional theories popularised by Kimberlé Crenshaw. And although heretics are unlikely to be burned at the stake, their inquisitors are convinced that non-believers must convert for their own good.

All of this amounts to the legitimisation of bullying on a grand scale. American physicist Steven Weinberg famously remarked that ‘with or without religion, good people can behave well and bad people can do evil; but for good people to do evil – that takes religion’. When the puritans descended on churches across the United Kingdom in the mid-seventeenth century, destroying paintings, statues, stained glass, and any other images deemed offensive to their creed, they were not necessarily doing so out of a juvenile relish for vandalism. Many believed that they were undertaking God’s work, and that their values should be imposed on the populace for its own sake.

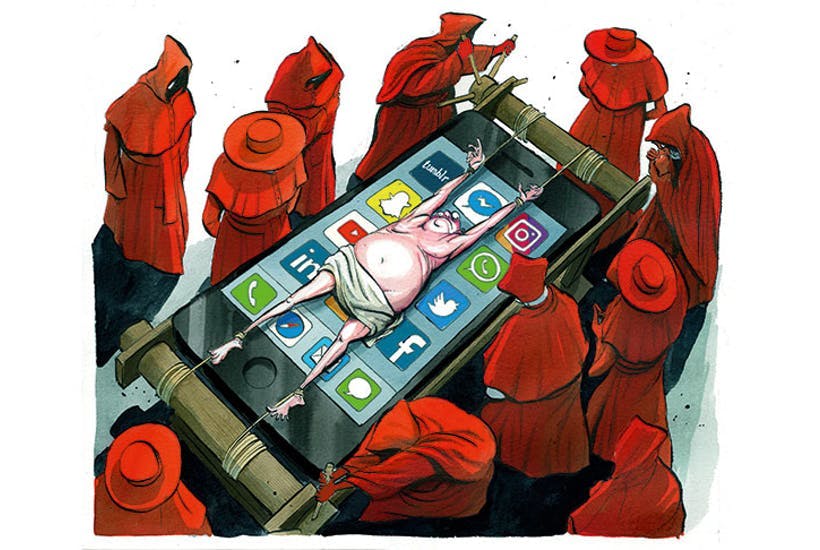

So too our latter-day puritans, who are happy to demolish the problematic monuments of the past, and scour social media for prey, like so many vultures circling their barely breathing lunch. They are the clergy for the digital age, an elite class that claims to know what is best for the unlettered plebeians. The trouble with all such righteous causes is that they attract the bullies who seek an approved outlet for their baser instincts. Some don the sacerdotal robes out of a sense of duty, others as a disguise.

Social media is the playground turned battlefield for these online crusaders. Here they pontificate to the masses, berate those who fall short of their moral expectations, and endlessly trawl through old tweets or Facebook posts in the hope of discovering a misjudged phrase or sentiment that could justify a campaign of public shaming. In their eyes, there is no possibility of redemption. The most vicious remarks you will find on social media come from the racist far right and intersectional activists. They are two faces of the same chimera. Identitarians on the right and left have an interdependent relationship; each one nourishes and sustains the other.

That is not to suggest some kind of moral equivalence. One of the most tragic aspects of this movement is that many of its acolytes are well-meaning. Yet unlike the culture warriors of the far right, who are universally despised in civilised society, the ‘woke’ religionists have positioned themselves as being ‘on the right side of history’ and therefore enjoy major institutional support. In spite of being capable of the most horrendous dehumanising behaviour, many of them believe themselves to be ‘the good guys’. With this paradox in mind, the prospect of putting an end to the culture war seems Sisyphean. How does one tackle a bully who bullies others in the name of love?

These cultural revolutionaries are engaged in an ongoing collective effort to destabilise and reorganise society around their ideological principles, underpinned by the conviction that the powerful – defined solely by group identity – are unaware of the structures that they unwittingly perpetuate. In this battle, however, the chief antagonists consider themselves to be under siege. In this perverse formulation, the defence of liberal principles is taken as an attack. This is why those who object to these radical and divisive societal upheavals are so often accused of ‘starting a culture war’, when they are simply responding to it. The new puritans are brawlers with a persecution complex, wildly throwing punches at strangers and then blaming them for the bloodstains on their hands.

We hardly even know what to call the movement, because this culture war is largely being waged through the subtle – and sometimes not-so-subtle – redefinition of language. The new puritans have become adept at the reapplication of existing terms that deviate from their widely accepted meanings. Phrases such as ‘social justice’, ‘anti-racism’, ‘liberalism’, ‘whiteness’, ‘violence’, ‘safety’, and endless others, now bear connotations that are understood only by a minority of activists. They have apparently taken their cues from Humpty Dumpty in Lewis Carroll’s Through the Looking Glass (1871). ‘When Iuse a word’, he says to Alice, ‘it means just what I choose it to mean – neither more nor less’.

When most of us say ‘social justice’, we mean the concept of equality under the law, opposition to prejudice and discrimination, and equal opportunities for all. When social justice activists say ‘social justice’, they mean an emphasis on group identity over the rights of the individual, a rejection of social liberalism, and the assumption that unequal outcomes are always evidence of structural inequalities. When most of us say that we are ‘anti-racist’, we mean that we are opposed to racism. When ‘anti-racists’ say they are ‘anti-racist’, they mean they are in favour of a rehabilitated form of racial thinking that makes judgements first and foremost on the basis of skin colour, and on the unsubstantiated supposition that our entire society and all human interactions are undergirded by white supremacy. No wonder most of us are so confused.

For the logomachists of the new puritanism, the ambiguity is the point. Where there are no shared definitions there can be no possibility of discussion. This strategy of destabilising language and its meaning enables the well-versed to befuddle the layman with jargon, thereby giving vacuous theories the impression of substance. Moreover, the ambiguity can act as a get-out clause to make statements that are otherwise bound to be interpreted as hostile. This is why the Cambridge academic Priyamvada Gopal can write phrases such as ‘Abolish whiteness’ and ‘White Lives Don’t Matter. As white lives’, and then blame those who are offended for being insufficiently schooled. That is not to suggest that she is insincere in her views, but one can appreciate from this example how such buzzwords can be readily exploited by those with an agenda.

So it has come to this. Liberalism is akin to Nazism. Words are violence. Debate is a fetish. We have somehow found ourselves in this mystifying scenario in which self-declared ‘liberals’ are advancing an illiberal agenda, ‘leftists’ are failing to stand up for left-wing ideals, ‘social justice’ means the opposite of what it says, and ‘anti-racists’ are creating a more racist society. The old definitions no longer apply. Culture warriors of all political affiliations play high-stakes word games, and truth and rationality are the casualties. We are dealing with a rapidly developing religion, albeit one of the secular kind, whose abstruse language and peculiar rituals are as incomprehensible to us as the miracle of transubstantiation must have been to a medieval congregation. This is a contemporary form of hocus pocus: we are tasting wine while the clergy assures us it is blood.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

This article is an extract from Andrew Doyle’s latest book, ‘The New Puritans: How the Religion of Social Justice Captured the Western World’, out now.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in