Productivity growth is the key to income growth – we can’t have the latter without the former. A matter that has troubled many economists in the Western world during recent decades is a slowdown in productivity growth.

Australia is typical. Multi-factor productivity – the overall return on labour and capital inputs combined – has been growing at only 0.3 per cent per year in recent years, while the more commonly understood, labour productivity, has also seen growth at only 0.9 per cent a year. These are half the levels seen in the 1990s.

That slowdown is less evident in many countries that are nowadays referred to as ‘developing’. Some such countries that had been lagging behind Western world living standards for centuries started to catch up once their governments stood back from directly controlling their economies and created the conditions for individuals to accumulate savings and to invest these with much reduced fears of expropriation.

First, beginning in the 1960s, we saw the so-called Asian Tigers – Hong Kong, Taiwan, Singapore, Korea – start to emerge as industrial powerhouses; these countries now have income levels that surpass those of most developed western economies. This was followed by phenomenal growth rates achieved by China; in more recent years we’ve seen India, Vietnam, Indonesia, and even some African countries starting to show high levels of economic growth.

In contrast to the liberalisation and lessening of investment constraints and regulations that powered those nations’ growths, most western economies have imposed increasing layers of regulation on investment opportunities. These measures have forced down investment returns through requiring additional spending on environmental, heritage, and social matters – including the preparation of lengthy reports – and lengthening the approval time required to operationalise an initial idea.

For Australia, the slowdown in per capita growth has taken place notwithstanding increases in investment. Per capita annual real capital expenditure is currently 50 per cent higher than in the late 1980s.

But much of the investment in recent years is simply in dead-weight assets like the many idle desalinisation plants that have been constructed around Australia, plants that owe nothing to commercial decisions.

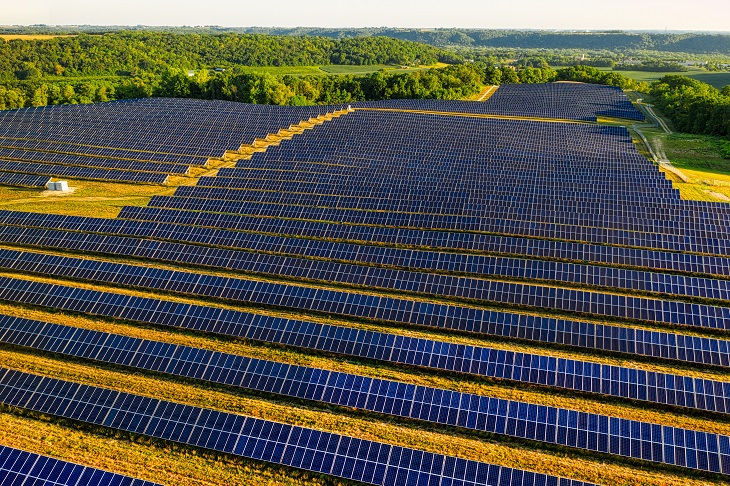

For the rest, increasing red tape reduces the efficiency – the payoff – of nearly all investment. And using subsidies to force funds into particular venues can lead the investment to have a negative effect by destroying the productive capabilities of other investment. This can be seen with new investment in electricity, which dominate the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS)category: ‘electricity gas, water, and waste services’. The category comprises about six per cent of Australia’s total new investment the bulk of which is for weather-dependent wind and solar and for the increased transmission, batteries, and pumped hydro necessary to support these generation sources.

This expenditure would not take place without subsidies either from government directly, or from regulatory measures that pass the costs of transmission and wind/solar onto consumers. In favouring these intrinsically high-cost forms of electricity, the subsidies force out of the market lower cost and more reliable forms, especially coal generators that comprise 60-70 per cent of supply. This has resulted in overall generation costs trebling and in measures to facilitate wind/solar that include replacing the present transmission system, valued at some $21 billion, with one at a cost that the government says will be $80 billion.

Regulations and direct subsidies to wind/solar have already forced the closure of coal generation capacity and the number of coal generating units in Australia is expected to be half their level of 10 years ago by 2025. On top of this is the Queensland Government’s radical plan to replace all its coal stations by wind/solar and two mythical pumped hydro schemes.

In measuring new capacity from investments, the ABS assumes its returns are constant and invariant to time, and ‘a change in the quantity of capital services delivered from any given capital asset is tantamount to a change in its productive capital stock’.

The sad fact is that certain investments, especially those taken for political purposes, yield no return at all and others are akin to investing in computer viruses that actually destroy value and cause considerable extra expenditures in attempts to offset the detrimental effects of the malware.

Subsidised expenditures in weather-dependent renewable facilities, rather than constituting investments, are parasitic outlays that destroy genuine income-producing assets.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in