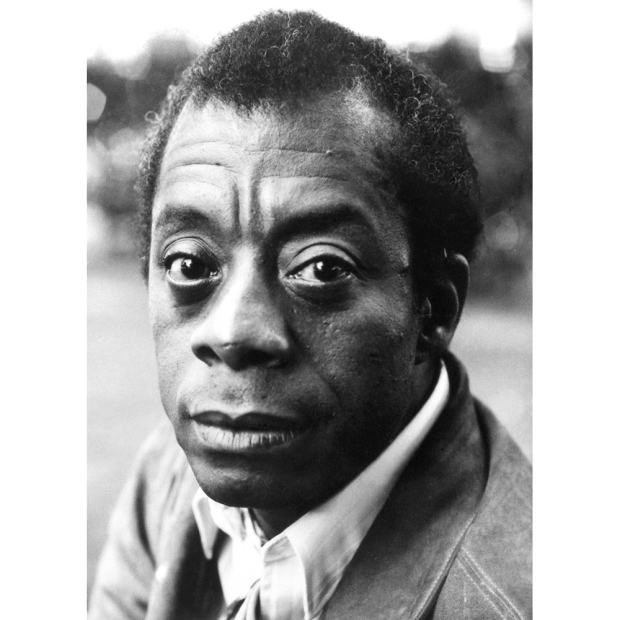

Huddie Ledbetter, better known by the prison moniker Lead Belly, was a musical genius born in the southern United States just as Jim Crow laws were starting to bite. He fell foul of an unapologetically racist legal system and ended up serving on a chain gang in 1915, later doing time in state penitentiaries in Texas (1918-25), Louisiana (1930-34) and at Rikers Island in New York (1939).

Already a subscriber? Log in

Subscribe for just $2 a week

Try a month of The Spectator Australia absolutely free and without commitment. Not only that but – if you choose to continue – you’ll pay just $2 a week for your first year.

- Unlimited access to spectator.com.au and app

- The weekly edition on the Spectator Australia app

- Spectator podcasts and newsletters

- Full access to spectator.co.uk

Or

Unlock this article

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in