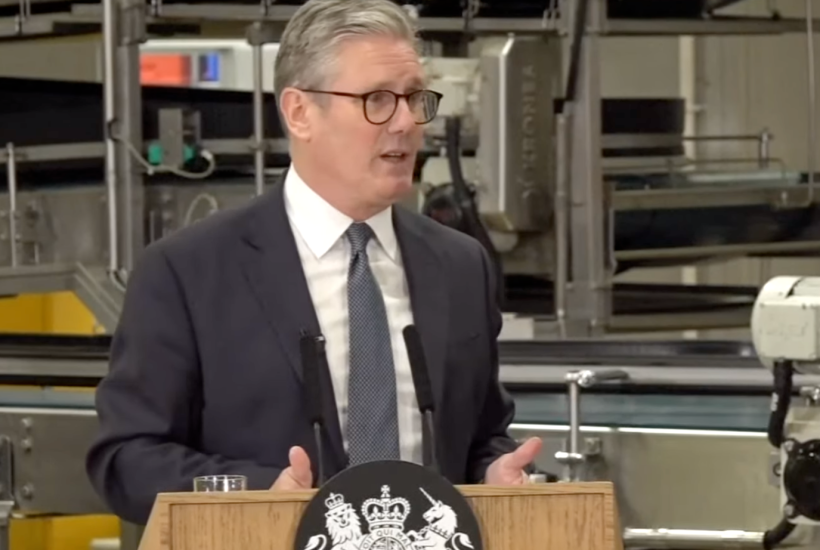

The Prime Minister is in Liverpool today, outlining plans for green investment. Nearly £22billion is pledged for projects to capture and store carbon emissions from energy, industry and hydrogen production. This includes funding for two ‘carbon capture clusters’ on Merseyside and Teesside over the next 25 years. Ministers hope this will create new jobs, attract investment and hit climate goals.

Already a subscriber? Log in

Subscribe for just $2 a week

Try a month of The Spectator Australia absolutely free and without commitment. Not only that but – if you choose to continue – you’ll pay just $2 a week for your first year.

- Unlimited access to spectator.com.au and app

- The weekly edition on the Spectator Australia app

- Spectator podcasts and newsletters

- Full access to spectator.co.uk

Or

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in