The two trendiest words in classical music are ‘El Sistema’. That’s the name for the high-intensity programme of instrumental coaching that turned kids from the slums of Venezuela into the thrilling Simon Bolivar Youth Orchestra (SBYO), conducted by hot young maestro Gustavo Dudamel before he was poached by the Los Angeles Philharmonic.

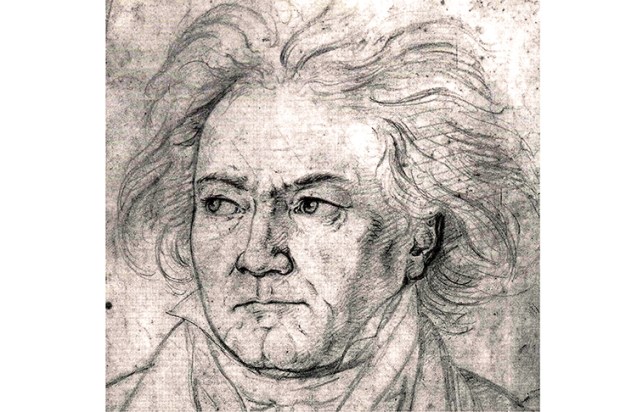

Or so the legend goes. When the SBYO was booked for the Proms in 2011, the concert sold out in three hours. Sir Simon Rattle, no less, declared El Sistema to be ‘the most important thing happening to classical music anywhere in the world’. Audiences wept at the sight of former street urchins producing a tumultuous, triumphant — and virtually note-perfect — performance of Beethoven’s Fifth. ‘If people cry two minutes into the concert, there’s nothing more to say,’ declared Rattle.

But it turns out that there is more to say, though it was last week before anyone spelled it out. The musicologist Geoff Baker has just written a heavily footnoted academic study of the Venezuelan ‘miracle’ entitled El Sistema: Orchestrating Venezuela’s Youth. Baker and his publishers, Oxford University Press, did not leak its contents in advance. El Sistema has powerful and very rich sponsors who might have blocked publication. But OUP’s lawyers crawled over every page. They had to.

Baker portrays El Sistema’s founder, the 75-year-old Jose Antonio Abreu, as a bully and political sycophant whose ‘system’ subjects children to brutal practising regimes that went out of fashion in the West decades ago. It’s more of a state-sponsored cult than a philanthropic marvel, says Baker.

Most disturbingly, he alleges that El Sistema permits the sort of sexual abuse of young musicians by their teachers that has recently come to light in British classical music circles — especially at Chetham’s school in Manchester. ‘Chet’s’, a co-ed specialist school that has produced some of this country’s finest musicians, has become synonymous with abuse. Its former choirmaster, Michael Brewer, was jailed for six years last year on five charges of indecent assault. His ex-wife, Kay, was also jailed for joining in the abuse.

Their accuser, Frances Andrade, claimed to have been assaulted by both of them when she was a violin student at Chetham’s in 1979 and 1980. Brewer dismissed her as a ‘fantasist’. Halfway through the trial she took a fatal overdose of prescription drugs. In September this year the conductor Nicholas Smith, another former Chetham’s teacher, was jailed for sexually assaulting a 15-year-old pupil. Two more individuals connected with Chetham’s have been charged, and there is also an ongoing matter in relation to one individual who resides outside of the UK.

Geoff Baker’s book specifically compares El Sistema to Chetham’s. He argues that both institutions have hidden classical music’s ‘dirty little secret’ — that the intimate, overwrought relationships between mentor and pupil encourage sexual abuse. One ex-Sistema musician describes the programme as a ‘chain of secrets and favours — like a secret society’. Baker writes: ‘She claimed that …young musicians regarded the trading of sexual favours as an unremarkable, even humorous, subculture within the orchestra. She mentioned so-called niños bonitos (pretty boys) appearing with brand-new, expensive instruments: “you think, there’s something more going on there than just talent”.’ A spokesman for El Sistema said last week that suggestions of widespread abuse were ‘absolutely false’.

Baker’s allegations feature prominently on the website of Ian Pace, head of performance at London’s City University and a virtuoso pianist specialising in the farthest reaches of the avant-garde. Pace is a campaigner against child sexual abuse — and conspiracies to hush it up. His Twitter account churns out allegations about paedophile sex rings in Westminster and the arts world. His enemies dismiss him as a left-wing crank, pointing to the ideological flavour of his campaigns against abuse-ridden hierarchies. Baker is also on the left: his exposé of El Sistema is a plea for progressive and experimental musical education. (The irony, he points out, is that Abreu’s liberal admirers think this is just what he has given Venezuela, whereas in fact he forces his pupils to worship the ‘elite’ classical canon.)

But Pace’s blog about sex abuse, Desiring Progress, is not the work of a crank. Its centrepiece is a petition for an inquiry into ‘sexual and other abuse at specialist music schools’. Signatories include Imogen Cooper, Peter Donohoe, Paul Lewis, Leon McCawley, Steven Osborne, Charles Owen, Martin Roscoe and Kathryn Stott — that is, most of Britain’s front-ranking pianists, plus the international virtuosos Andrei Gavrilov and Marc-André Hamelin. Other signatories include the oboist Nicholas Daniel, the cellist Steven Isserlis and the violinist Tasmin Little, all world-class soloists. The composer Michael Berkeley has signed: he’s now a peer and free to name names in the Lords without fear of libel action.

Pace, not coincidentally, was educated at Chet’s. ‘From very early in my time at Chetham’s I could tell something was wrong, creepy, unsettling about the place, the people and the culture,’ he says.

‘Many teachers were smarmy, arrogant, but charismatic and “artistic”. They’d fawn over certain pupils, not simply because of admiration for their musical achievements. Rather those pupils became objects of desire, groomed for purposes of delectation and titillation. With that came a type of premature sexualisation, in terms of the figures pupils were expected to cut on stage, and the need for them to communicate sexualised adult passions and desires through music. The ability to do this, to play this game, seemed to create a type of pecking order.’

According to Pace, this mindset permeates classical music. ‘When I have heard the ways in which various teachers, critics, those in charge of musical institutions, and others speak of many child or young performers, the thinking can itself be predatory.

‘People and their musicianship are summed up in terms of being a “bit of rough”, a “pussycat”, a “tease” and so on. One teacher openly berates one male student for not getting “fucked enough”, claiming that their artistry is limited for this reason.’ And some women teachers play this game, he adds: ‘One deeply insecure female teacher resented seeing her younger male students with girlfriends, and would surreptitiously intervene in their lives to try and wreck their relationships. And of course to criticise some teachers can be fatal in a world where careers are already deeply precarious.’

Sexual abuse in music schools is often an extension of other forms of abuse, says Pace — psychological, emotional and physical domination disguised by the mystique of the ‘artistic’. This rings true: substitute the word ‘spiritual’ for ‘artistic’ and you have at least a partial explanation for the epidemic of molestation in the Catholic Church. Tutors in music colleges are more than teachers: like clergy, they are called upon to exercise authority in an intimate setting. Pupils sometimes ascribe quasi-magical powers to them. It’s worth stressing that most teachers are not tempted to make sexual advances to their young charges; that most of those who experience temptation resist it; and that, as crimes are uncovered, blameless people face the terrifying prospect of made-up allegations.

All of which lends urgency to Pace’s demand for a thorough inquiry — and a restructuring of musical education to safeguard pupils. The signs are that classical music is about to suffer the convulsions experienced by the Church and BBC light entertainment. The past is being raked over. No one imagines that Benjamin Britten will emerge as the Jimmy Savile of high culture, but not everyone believes that his passion for prepubescent boys was weird but sublimated and therefore innocent, which is the contorted position of the Britten estate. What are we to make, for example, of the diaries of the notorious paedophile Peter Righton, which refer to Britten and Peter Pears as friends and ‘fellow boy-lovers’?

More significantly, the police have fat dossiers on current figures in the music world. Other suspected crimes have yet to be reported. ‘I am aware of allegations, some very serious and of a sexual nature, against prominent teachers working right now in various of the leading UK conservatoires,’ says Pace. In February this year, former Guildhall School teacher Philip Pickett — a hugely respected director of early music ensembles — was charged with eight counts of indecent assault, three counts of rape, two counts of false imprisonment, one count of assault and one count of attempted rape. Pickett’s trial has been postponed from October 2014 to January 2015 so that he could finish touring — a ruling that Pace describes as ‘quite incredible’.

We must, of course, presume Pickett’s innocence, but his trial will certainly focus attention on charges of abuse at British music schools and beyond. Meanwhile, it will be interesting to see how institutions such as the Southbank Centre that have championed El Sistema — and Sistema Scotland and Sistema England which are modelled on the SBYO — react to Baker’s meticulously researched book. There is a lot of money worldwide invested in this brand — enough to withstand most allegations. But, as the Catholic Church has discovered, the exposure of child abuse changes everything.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in