When presented with a 639-page doorstopper which includes 82 pages of closely-written sources, notes and index, most of us feel a bit like a patient about to swallow a strong dose of antibiotics: ‘This isn’t going to be pleasant, but it’ll be good for me.’ First published in Dutch in 2010, translated into French and German, and only now coming out in English, Congo arrives trailing prizes and praise. And yet I quailed.

What I hadn’t realised was that David Van Reybrouck, who spent a decade on this extraordinary work, is not primarily a historian. He is a playwright, poet and novelist and, if this translation by Sam Garrett is anything to go by, has a beautiful feel for language (I loved the description of the soil-laden Congo river as ‘rusty broth’). After a rather slow start, his eye for the arresting human detail, combined with a wry appreciation for a peculiarly Congolese form of gumption, keeps you powering through this panoramic survey of 150 turbulent years.

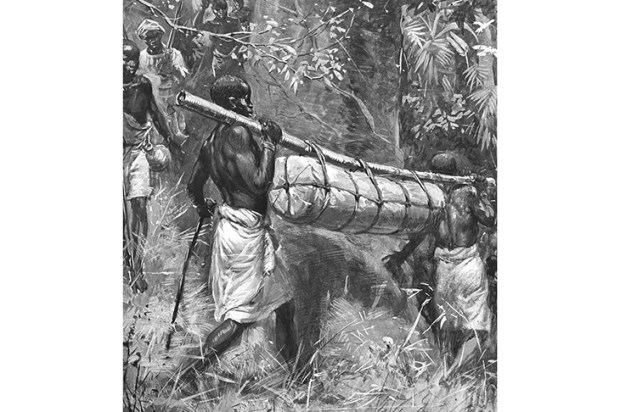

The story of how King Leopold II carved a colony the size of Western Europe from a Central African river basin, milking it of ivory and rubber before handing it to the Belgian state, which granted hasty independence and paved the way for Lumumba, Mobutu and Kabila père et fils, has been told before. If it feels fresh in these pages it is largely thanks to Van Reybrouck’s decision to seek out rarely heard first-hand testimony.

It’s an approach fraught with risk, as he acknowledges. Memories shift. In close-knit communities, what happened to a distant cousin blurs easily into what happened to you. But Van Reybrouk does his best to buffer his on-the-ground perspectives with documented facts — hence those 82 pages of notes — and the resulting foot soldier’s view of great events feels both intimate and immediate.

So we get Papa Nkasi, so old he met the turn-of-the-century prophet Simon Kimbangu; André Kitadi, a wireless operator in the Force Publique who spent three months in 1943 trucking from Lagos to Cairo as part of the Allied war effort, and Alphonsine Mpiaka, the first Congolese female paratrooper, trained to parachute by the Israelis.

Congo is not imbued with the blazing anger of some histories of the country, and that comes as a relief. The American writer Adam Hochschild covered that ground so thoroughly in King Leopold’s Ghost, which tracked E.D. Morel and Roger Casement’s 19th-century campaign to halt the atrocities used to extract booty, there is little to add.

Some may judge Van Reybrouck, whose father worked on the Benguela railway, to be soft on his immediate ancestors, who replaced outright abuse with forced labour to extract Congo’s minerals. But the point about mature colonial powers is that so much harm was done with such very good intentions, by men and women who would be appalled at the modern-day assessment of their efforts.

I was glad to see Van Reybrouck, too, acknowledge that the early Mobutu was nothing like the cynical sybarite he became at the end. On the contrary, as a young man he ‘delivered a moral jolt to a nation in disrepair’, launching a series of massive infrastructural projects, doing away with ethnic division in army and education, and managing, via his ‘authenticity’ programme, to create an abiding sense of national identity.

I have a few quibbles. Turning to ‘the first African world war’, as the complex conflict which broke out in 1998 is sometimes termed, Van Reybrouck falls into a much-frequented trap, reporting that ‘as many as five million people have been killed in hostilities’. The International Rescue Committee is the source of that staggering statistic and it has always made clear that most deaths were civilian, involved children under five, and were caused by preventable diseases — a nuance Reybrouck himself acknowledges. This tragedy is one of negative development exacerbated by war rather than the testosterone-fuelled conflict that the phrase ‘killed in hostilities’ implies.

The book closes with a fascinating account of a trip to Guangzhou, China, where the author discovers a community of 2,000-3,000 Congolese traders who spend their days loading containers with mobile phones, cheap clothing, computer parts and tomato paste for export to Congo. So vibrant is the trade, he meets a hyperactive young Chinese salesman who, installing SIM cards and replacing batteries, speaks to him the while in fluent Lingala.

China’s African legacy will be the stuff of many future books, but I couldn’t help feeling Van Reybrouck placed too much emphasis on the transformative potential of this entrepreneurial exchange. The Congolese are partly brilliant small traders by default, because this is one of the few areas to escape a predatory state. If Congo is to break free of its current predicament, it will need more than individual survival skills, however inspired.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Available from the Spectator Bookshop, £20. Tel: 08430 600033. Michela Wrong is the author of In the Footsteps of Mr Kurtz: Living on the Brink of Disaster in the Congo.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in