John Ford was the first of the five famous Hollywood film directors to go to war. He went expecting to get given a sword, which he could then brandish. After all, he knew about swords; they were things that came out of props baskets in his cavalry epics, but that was in films. Unfortunately in real life he found he had an arthritic thumb, which meant that having once drawn one he needed help to put the sword back in its scabbard. It had not been like that in his films, where he had only to say the word for anything to happen. There he could put a coal mine on top of a mountain in How Green Was My Valley, and farm the desert in his Westerns.

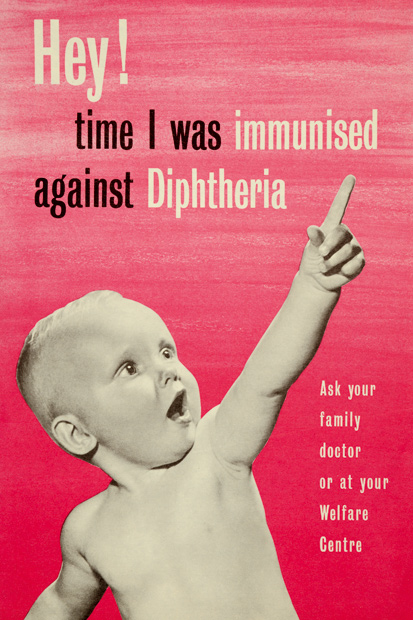

But the first film he made in the navy was real life with a vengeance. He obediently made a 26-minute short, with close-ups, on the dangers of VD for sailors, watched it through and threw up. Still he was the first of the five to see action, real action, when he filmed, in colour, the naval Battle of Midway. Congratulating him, the producer Walter Wanger told him that what he had done was award material, which allowed Ford to say smugly, ‘I just want to remind you Hollywood guys that someone’s out there fighting a war.’

Only then he himself forgot this, got plastered during D-Day and was thrown out of the navy. So what did he do? What any spoilt crackpot would do in the circumstances. Ford booked into Claridges and cabled his wife, ‘Sorta winding this thing up.’ At times, whatever it sets out to be, Five Came Back is a funny book because of the tension between film, which the five knew all about, and life, about which they knew far less.

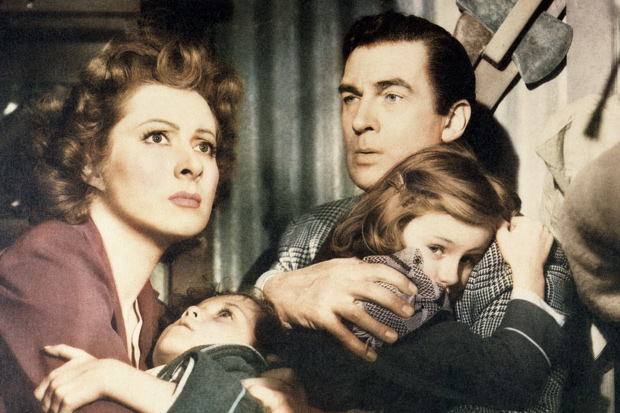

The novelist Irwin Shaw, working with a film unit, encountered this when he saw his first corpses. ‘They were all mangled, and both very young, and we took pictures.’ Of course the Nazis, unable to distinguish film from real life, were at an advantage here. Lillian Hellman thought William Wyler’s sentimental Mrs Miniver ‘a piece of junk’, and the director himself considered it over-glamorised, but Goebbels thought it ‘an exemplary propaganda film’. Propaganda came naturally to loonies living in a world of their own; Frank Capra realised how much better the Germans were at it when he saw The Triumph of the Will, and said, ‘We’re dead. We’re gone. We can’t win this war.’

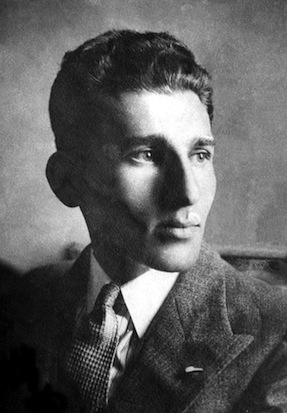

The result was that initially he had found himself tempted by the wrong side, when before the war Mussolini offered Columbia a million dollars to make his film biography, provided Capra directed. The Duce proposed to write the script himself. Capra, who had a picture of Mussolini on his bedroom wall, was keen, but the studio boss, Harry Cohn, turned the offer down, having remembered something (‘After all I’m a Jew’). Luckily Capra then met Roosevelt, who until that point had just been the man who took 80 per cent of Capra’s salary in income tax, ‘and the President’s awesome aura made his heart skip’: the film-makers were not totally rational men.

John Huston, who got himself into the Mexican cavalry, went to parties with a monkey on his shoulder, and married five times. George Stevens thought he had Red Indian ancestry, so as a director he had been totally silent on set, unnerving his actors.

Still they made their war films, the most famous being William Wyler’s Memphis Belle about the last active service operation of the crew members of a Flying Fortress who, having completed 25 missions, were being stood down. Wyler went with them and the crew could hear him over Germany asking the pilot to fly closer to the flak so he could get a better picture. The five directors, a whole generation older than the men they were filming, were brave, being, as I say, not totally rational men.

I met the crew of the Belle when they came over to this country in 1990 to publicise the remake of the picture. They were old by then and their most vivid, bitterest memories were not the fear or the dying that a half century earlier had been part of their daily lives, but something they had been made to eat, also on a daily basis. Most other things had slipped away, for the youngest of them had only been 19, but brussels sprouts were as horribly vivid as though they had been yesterday. The flak appeared to have been forgotten.

The funniest thing in this book is the author’s description of a speech by Dorothy Parker to the Anti-Nazi League when she could not bring herself to mention Hitler’s name but instead kept referring to ‘that certain man’. The old newspaper hand, searching for the most complete revenge, had taken away his byline.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Available from the Spectator Bookshop, £23. Tel: 08430 600033

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in