In February 1924 the Hotel Florida, a ten- storey marble-clad building with 200 rooms, a glass-roofed atrium and red plush furnishings, went up on Madrid’s Gran Via. Along with the Ritz in Paris, certainly the most celebrated hotel in the literary world, the Florida became, during the two-year battle for the capital waged between Franco’s nationalists and the republican forces, the meeting place for an eccentric, glamorous and self-important assortment of war tourists, zealots, opportunists, romantics, dreamers, buccaneers and writers who had come to observe the fighting, file dispatches of variable truthfulness and proclaim loyalty to the republic. In its own way, the Florida has become as emblematic of the Spanish civil war as Robert Capa’s controversial photograph of the militia soldier shot as he leaps across a ditch.

Six of its visitors form the basis of Amanda Vaill’s new account of the war, brought to the Florida by a shared commitment to the cause and their own particular ambitions and dreams. There are Hemingway and Martha Gellhorn, the best known couple, whose exploits and murderous quarrels have been amply chronicled elsewhere. More interesting, there is Arturo Barea, tormented night-time censor in the propaganda department, whose job it was to ensure that nothing got out of Madrid that suggested anything other than a republican victory, and Ilse Kulcsar, a curly-haired Austrian political exile with whom he fell in love, who spoke eight languages and had come, as she saw it, to bear witness. Barea makes an attractive character, railing against the levity and posturing of the foreign reporters, behaving as if they were the ‘main actors in the war’.

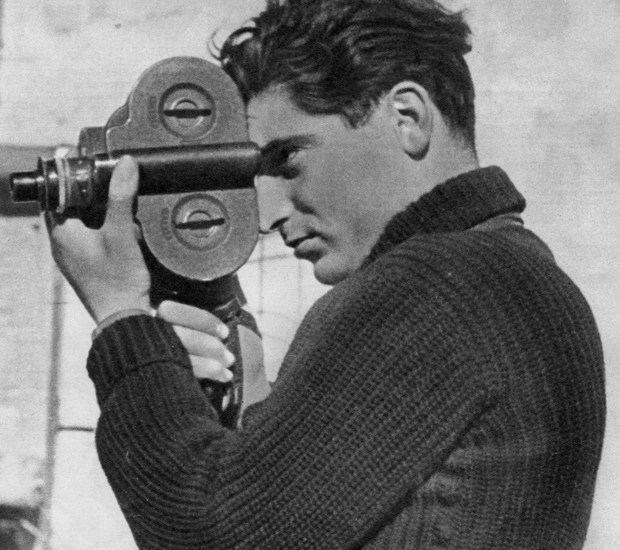

And there was Robert Capa, the dark and very attractive Hungarian photograher, who had just turned 23 and changed his name from André Friedmann, thinking Capa sounded crisper and more memorable, who arrived with the boyish and foxy looking Gerda Taro, who had also changed her name, from Gerta Pohorylle, for much the same reasons. Their plan was to chronicle the miseries of war and use their photographs to make their names in the new European and American picture magazines.

Around these three couples swirl a vast cast of characters, some — like Dos Passos, Lillian Hellman and Mikhail Koltsov, much written about — and others — Spanish officers, Russian commissars, the men and women who fought and died in Spain — whose stories Vaill has painstakingly unearthed in the archives. One of the pleasures of her book is the amount of detail she has woven into the two and half years of her story, as she flits between Madrid and Barcelona, Paris and Key West, Moscow and Valencia.

Not all of the Hotel Florida’s visitors had much interest in telling the truth. Certainly not Hemingway, whose desire to support the republicans made him willfully blind to their own atrocities; nor Barea, though he grew increasingly frustrated by his role as censor; nor the Russian commisars, intent on obscuring Stalin’s real war aims. It was in Spain that Gellhorn coined her memorable phrase ‘all that objectivity shit’. This was not the age of embedded war reporters, and those who went to the civil war wandered more or less at will, filing the stories that for them mattered the most. For Gellhorn, as for Hemingway, what was important was not reporting all they saw, but of influencing western governments to support the losing republican side.

On 27 March 1939 Madrid at last surrendered to the nationalists. As Franco and his troops rounded up, imprisoned and set about executing thousands of republicans, the US recognised him as the head of the legitimate government of Spain. Gerda Taro — whose considerable contribution to the remarkable series of photographs sent back and published in Vue, Time and Life has only recently come to light with the discovery of a lost suitcase of negatives — was dead, crushed by a tank as she drove away from the battle of Brunete. Internment camps had opened across the border where the French were giving grudging shelter to thousands of destitute and grieving Spanish refugees.

In August, Germany and the Soviet Union signed a non-aggression pact and many of the Russians described by Vaill, who had acted with such wily and brutal diplomacy among the Spaniards, had gone home to be murdered in Stalin’s purges. Ten days later, the war in Europe, for which, as Gellhorn had remarked, Spain had been the desperate dry run, was declared.

By now, Hemingway was hard at work on For Whom the Bell Tolls, whose immense success would do much to assuage a long period of poor sales and bad reviews; and Gellhorn, whom he was to marry as soon as his divorce from Pauline came through, was preparing to cover another war, this time in Finland. Capa was wandering, mourning Gerda, towards other equally brutal battles. Barea and Ilse had married and escaped to England, to spend their time writing memoirs and short stories.

Though the Hotel Florida was eventually demolished, to make way for a new department store, Hemingway returned to the room he had once shared with Gellhorn, bringing Mary, his fourth and last wife with him. The bombed rooms and scarred walls had been patched up and Madrid was again a handsome city; but the political scars of its inhabitants would continue to resonate long into the future.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Available from the Spectator Bookshop, £20. Tel: 08430 600033. Caroline Moorehead is the author of Martha Gellhorn: A Life.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in