We owe Constant Lambert (1905–1951) a huge amount, and the flashes of brilliance that survive from his short life only suggest the energy with which he established the possibilities for English culture. What we remember about this extraordinary man are some delightful pieces of music, especially The Rio Grande; the funniest and most cultivated book about contemporary music ever written, Music Ho!; and a few surviving recordings of his work as a conductor.

Before his death, aged 46, from chronic alcoholism and undiagnosed diabetes, he had established the Sadler’s Wells Ballet with Ninette de Valois and Frederick Ashton; in the trio, he was not only the conductor and musical expert, but someone who was acutely alive to the possibilities of stage design and drama. He survives as a sort of in-between figure, coming after the English visionary genius of Elgar and Vaughan Williams and before composers with the international stature of Britten and Tippett. From reading about this life of extraordinary professional energy, it became clear to me that Lambert almost single-handedly created openings for a later generation.

He was obviously a fascinating person. After his death, many of his friends tried to pin down the louche charm of his conversation, his broad interests and his wit. Best of all are two portraits by his friend Anthony Powell — the first as the character Hugh Moreland in A Dance to the Music of Time, the second under his own name in Powell’s memoirs. The bawdy, cultured, rueful world around Lambert is beautifully captured, as well as his bad luck. The sort of absurd joke he relished is nicely summed up thus:

Lambert especially enjoyed putting forward subjects for Royal Academy pictures in the sententiously forcible manner of Brangwyn, of which two proposed canvases were Blowing Up the Rubber Woman and ‘Hock or Claret, Sir?’: Annual Dinner of the Rectal Dining Society.

His wit happily survives in Music Ho! — a book which is often wrong, but very persuasive — as well as in a run of music reviews, as incisive, knowledgeable and funny as any of George Bernard Shaw’s: ‘The gear-change between the first and second subjects would have made a dead French taxi-driver turn in his grave’ is a typical example. The jokes almost always serve to make a penetrating point. Only a very good musician could have come up with the one about most composers working at the piano, but Brahms working at the double bass; and there is a bold claim for the Busoni piano concerto being ‘the most important concerto ever written’.

There are also some very funny letters, which make one feel that a collection might be a good thing. Lambert was also capable of writing highly amusing verse to order, including some entertainingly abusive lines on the subject of Scottish music for Anthony Powell’s mock-Augustan verse Caledonia (‘And ev’ry puling crofter’s lad of ten/Aspires to be a Bartok of the Glen’); some ingenious limericks; and a Ballad of LMS Hotels, inspired by the suffering endured in Scottish wartime hotels (LMS being the London Midland and Scottish Railway):

There’s an LMS Hotel at Kyle of Lochalsh

Where beds are cold & bathrooms far

and few;

At the hotel in Gleneagles

They fricassée the beagles

And they charge you 10/6 for Irish stew.

All these suggest a wonderfully intelligent and funny companion, whose conversation is mostly lost but of whom it is recorded that when he saw a book entitled English Comic Characters. J.B.Priestley in Foyles’s window he ‘went inside and asked if they had Hugh Walpole in the same series’.

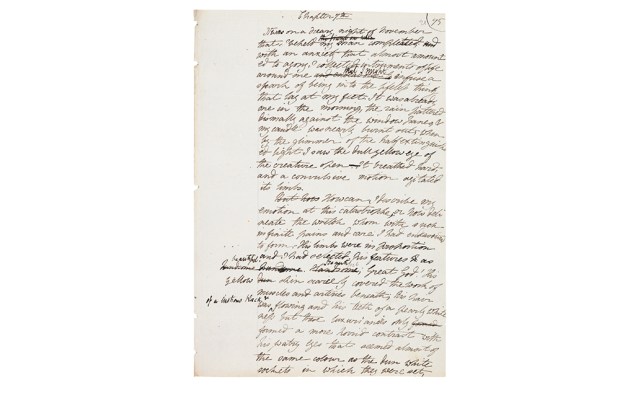

Lambert was near to being a child prodigy. Barely out of school, he was commissioned by Diaghilev to write a score for the Ballets Russes, though the relationship didn’t prosper; according to Osbert Sitwell, whenever a gap emerged later, Diaghilev would moan ‘Sûrtout — pas de Lambert’.But Lambert was soon established in London as a brilliant, cosmopolitan figure, the best narrator of his friend William Walton’s Façade and, aged 22, the author of the jazz-inflected piano-concerto-choral-fantasy The Rio Grande. This was a great favourite, performed a dozen times at the Proms in Lambert’s lifetime, and it still has an irresistible zing and pizzazz — notwithstanding its rag-bag construction and shameless thefts from Holst.

A career as a promoter of interesting new music, as a composer of sparkling inventiveness and as a critic had also to be combined with the busy life of a professional conductor. It was in 1928 that Lambert first conducted ballets for Ashton and de Valois, and over the next two decades he would take them from the occasional hired theatre to the apotheosis of the Sadler’s Wells style on the famous 1949 tour of America and Canada. His judgment and musical standards — surviving recordings of his Tchaikovsky ballets are thrilling in their lucidity and drive — were at the heart of the achievement.

What took the company as a whole to such a high level were, surely, the immense challenges it faced during the war. Astonishingly, in May 1940, Sadler’s Wells was ordered to tour Belgium and the Netherlands to raise morale, and found itself being ‘received with almost heartbreaking enthusiasm’ as the German invasion was poised to strike. The last performance of the tour, in Arnhem, was of Façade, that relic of camp 1920s fantasy. Afterwards, de Valois and the star, Margot Fonteyn, were presented with bouquets by an 11-year-old member of the Arnhem ballet class, later known as Audrey Hepburn. They left Arnhem at one in the morning and the Germans entered two hours later.

The company escaped the Netherlands by the skin of its teeth, alongside the fleeing Queen Wilhelmina, but that was not the end of its war contribution. The gruelling schedule endured by all its members must have been exhausting, but it drilled them to the highest standards and their discipline certainly astonished postwar American audiences. Such demands may well have contributed to Lambert’s early death.

This is a very detailed account of a working life. Lambert has been surprisingly well served by biographers, including the triple portrait by Andrew Motion that includes Constant’s father, George (a painter) and his son, Kit (manager of the Who). Stephen Lloyd gives us a satisfying number of letters both to and from Lambert, allowing us a sense of his enchanting voice.

Where Lloyd seems less at home is in the rackety world of Lambert’s drinking friends and his complicated love life. (Constant liked to say that, apart from Modest Mussorgsky, no composer had ever had a less appropriate first name than himself.) One feels as though one’s observing Lambert’s long and tempestuous affair with Margot Fonteyn from a remote distance, and at the end of the book one gets more of a sense of hearing Lambert conduct Tchaikovsky than of what it felt like to be married to him, or to finish a bottle of whisky in his company while arguing over Stravinsky’s merits.

Nevertheless, the milieu is fascinating, and the progress of this exceptional, unfulfilled talent bears any amount of detailed investigation. The one thing no biographer can explain is that a number of Lambert’s friends reported posthumous, ghostly interventions in their lives: Powell was apparently rung up by him after his death, and an unexplained black cat appeared at a concert performance of his Eight Poems by Li Po, sitting patiently on the stage during the music and leaving afterwards, never to be seen again. It was as if 46 years weren’t enough to contain this immense spirit.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Available from the Spectator Bookshop, £40. Tel: 08430 600033

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in